Are you applying to the No Waste Challenge in Tokyo?

In this brief summary, we dive deeper into local perspectives around waste, and highlight the specific challenges and opportunities facing this region.

Keep reading to learn more about submitting a project to the Tokyo city track.

BEFORE YOU APPLY WE RECOMMEND YOU FIRST READ:

TOKYO NOMINEES

TOKYO BRIEF

CURRENT SITUATION

MEGA-CITY, MEGA-CONSUMPTION

Tokyo is a global megacity with an area that covers some 2,194 km² and houses 14 million residents, making it the largest city in the world in terms of population. The urban setting contributes to a high amount of consumption and waste. The central area (23 wards) generate a total of around 3 million tonnes of municipal solid waste each year. This is enough trash to fill about 7.4 Tokyo Domes! About 70% of this waste comes from households, while the other 30% comes from shops/offices.

Let’s zoom in a little bit. What does this mean on an individual level? Each person in Tokyo generates close to 1 kg of waste everyday. In fact, Japan ranks 2nd globally in the volume of single-use plastic waste per person. Some efforts have been made to address the issue, including a few government initiatives focused on education and awareness. Thanks to this, the annual amount of municipal solid waste in Tokyo reached its peak in 1989 and has since decreased to around 3 million tonnes today. However, much more can be done.

We can still turn things around, if we act quickly. Currently, Tokyo has only one operating landfill that will meet its capacity in around 50 years. All this in mind, there is an urgency to think about waste in its pre-waste state and a necessity to guide materials back into a circular economy.

Challenges in tokyo

IMPORTING FOOD WASTE

In Japan, it is considered a courtesy and a virtue to finish every dish that is served during a meal. However, in reality, 1.3 billion tonnes of edible food is still wasted annually. In bustling Tokyo, industrial food waste from restaurants reaches up to 980 thousand tonnes annually, while households are responsible for 990 thousand tonnes.

Japan’s food self-sufficiency rate is approx. 66%, but if you look at Tokyo, this number drops to only 3%. There is a contradiction baked into Tokyo’s food system, where we import large amounts of food from outside the city, yet we throw them away without consuming them.

MANY REASONS BEHIND TEXTILE WASTE

In Japan, 940 thousand tonnes of clothing is disposed of every year. However, it is difficult to get an accurate figure for Tokyo because textiles are often thrown away as burnable trash.

This disposal is said to occur for a combination of reasons. Some of which are short cycle of consumption and production due to the rise of fast fashion, and a reluctance to sell or resell at lower prices in order to maintain brand value. In Japan, the import penetration ratio of clothing stands at 97%. About 60% of it is from China, while the rest comes from other Asian countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia.

THE SECOND LARGEST CONSUMER OF PLASTIC

Japan’s domestic consumption of plastic products reaches up to 10.12 million tonnes per year. By 2017, the amount of plastic packaging waste produced in Japan was second only to the United States. Until recently, most of this waste was exported to China for disposal. But since 2018, China and other Asian countries have begun to restrict imports, and plastic is now piling up at waste disposal plants all over Japan, while microplastics are flowing into Tokyo Bay. We are now faced with the mammoth task of securing disposal sites while reducing consumption.

INSIGHTS ON WASTE IN TOKYO

LOCAL INSIGHT

CONSUMER PRIORITY

Designers and manufacturers respond to consumer needs that are reflected in product preferences and shopping behaviors. It is in this sense that consumers are said to vote based on what they buy.

In Tokyo, the following factors are often considered as consumer priorities:

- Convenience

- Quality

- Sanitation/Cleanliness

The preference for convenience is best exemplified by the ubiquitousness of convenience stores. For example, there are close to 8000 convenience stores in the city, that mostly operate 24/7.

LOCAL INSIGHT

FEW OPTIONS

There has been a departure from a more sustainable lifestyle that existed when resources were limited, especially in cities where commercialization dominates. Products and systems are not designed with reduce, reuse or recycle in mind. Instead, the 3R’s are only applicable to things that have already been deemed as “waste”.

Consumers are often not provided with sustainable, alternative choices such as plastic-free, sell-by-weight, and bring your own bottles and containers. There are minimal behavioral nudges (incentives and restrictions) to take less because waste treatment costs are externalized as pooled tax expenses.

LOCAL INSIGHT

MAGICAL TRASH BIN

You will find that streets in Japan are clean, even without the provision of waste bins. Public littering is illegal, and so is the disposal of large items like furniture and e-waste without registration and payment.

In addition, a national budget of 2 trillion yen is allocated for municipal waste treatment each year. Tokyo’s highly sophisticated incinerators can even process plastic, at the expense of higher carbon dioxide emissions. This means that at home, for example, it doesn’t matter how much plastic you throw away, as long as you separate it. Unfortunately, the effect is that Tokyo’s ‘perfect’ waste management system is in fact reducing people’s awareness of waste.

GET INSPIRED by JAPANESE HERITAGE

LOCAL INSIGHT

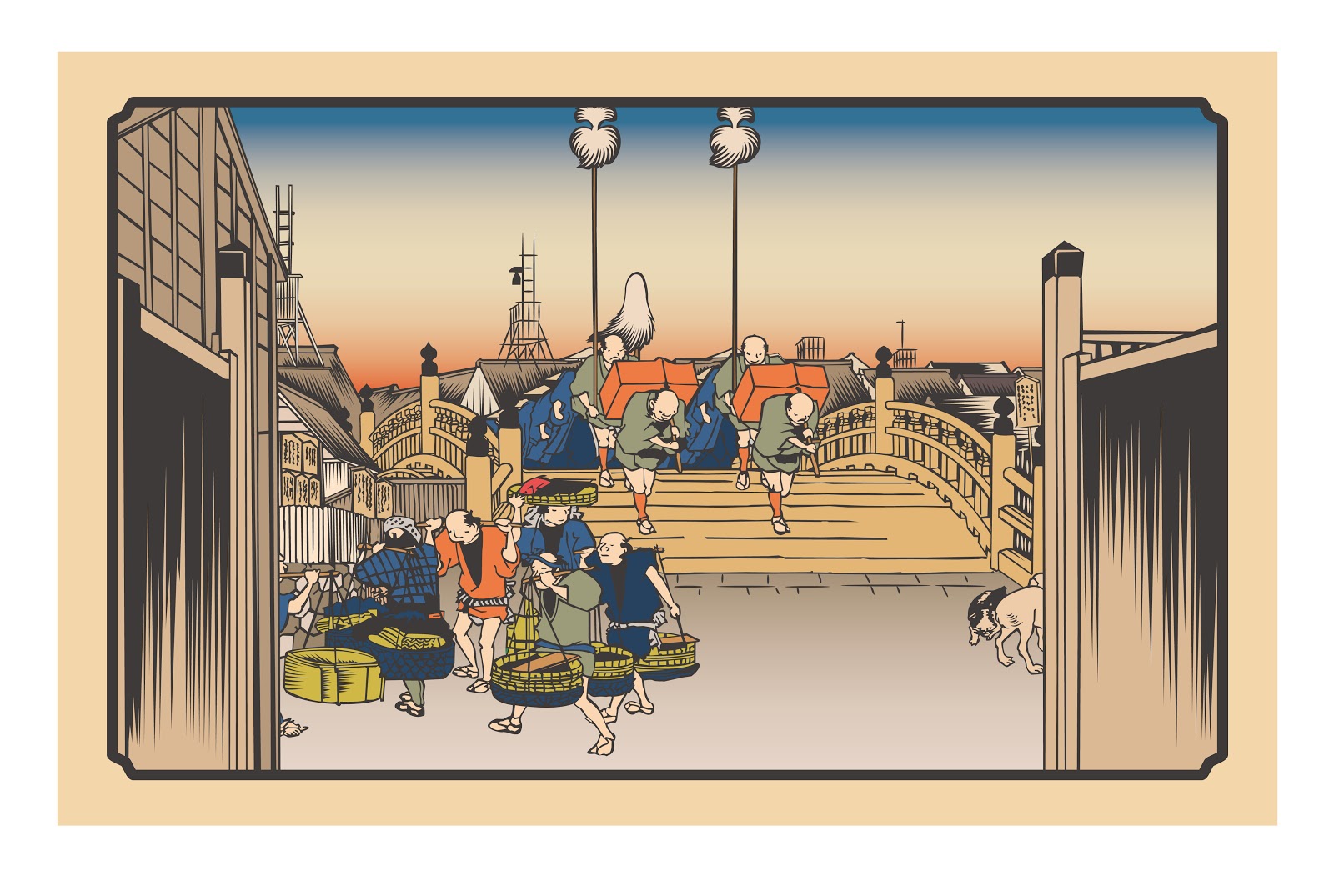

TOKYO WAS ONCE A RESOURCEFUL SOCIETY

Japan’s Edo period lasted from 1603-1868. The population of 30 million was said to be a resourceful community with the mindset of a circular society.

Back then, Japan had an active second-hand and recycling market and ecosystem. Material recycling, repair and reuse were widely practiced. This was made possible by a variety of occupations. For example, ash buyers collected ash from burned timber or waste to be used as fertilizers, fabric dyes, and for alcohol distillation.

Today, the second-hand market in Tokyo is mainly for materials like apparel, automobiles, and electronics. Are there ways for designers to activate new markets? How can designers normalize them and make them fun for consumers?

LOCAL INSIGHT

IN HARMONY WITH NATURE

Japan is a mountainous island surrounded by seas, and has developed its own unique culture in harmony with nature. In the riverside town of Gujo Hachiman in Gifu Prefecture, people have developed a lifestyle around the domestic use of spring and mountain water. From upstream to downstream, the same water is used over and over again but for different purposes, from drinking to washing clothes. As it goes downstream, the water is eventually used for farming, and completes a cycle by returning to the same waterways. This lifestyle in balance with nature makes the cityscape beautiful, and still fascinates people today. How can we stay in harmony with nature while utilizing our unique cultural values, within the constantly developing urban landscape of Tokyo?

LOCAL INSIGHT

MODULAR AND SUSTAINABLE AESTHETICS

Japanese architecture is closely related to its culture, and often fosters the Japanese sense of rationality and beauty.

Igusa, the material used for tatami, has a natural ability to regulate humidity, purify the air, and eliminate odors. And, if you take care of it, you can continue to use it for more than 20 years by turning it over when the front is worn out. It’s clear that the idea of sustainability as we know it today was also present in ancient Japanese practices. How can the wisdom and spirit of the past inherited in Japanese culture be applied to life today?

WHAT CAN DESIGN DO FOR TOKYO?

So where can designers make a difference?

With the help of our partners, we’ve highlighted some key opportunities and case studies relevant for Tokyo, but there are plenty more!

Refer to the global briefs for further inspiration.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR DESIGN

This design brief asks: how can we use natural resources that are available in Japan more wisely and consume mindfully? Take Tokyo’s needs into account by considering the following opportunities.

- Japanese consumers look for convenience, perfection, standardization, and high sanitary standards in their products. But this results in extensive packaging — and lots of waste. How can we create new incentives for consumers and producers to use less packaging materials?

- While we’re at it — remember that Japan ranks 2nd globally for the volume of single-use plastic waste per person. How can we boost the demand for plastic-free products?

- Tokyo is known to have many single households and a declining sense of community. How can we promote ways of sharing that are convenient and attractive to people living alone?

get inspired

NETWORK OF KINDNESS

Traditionally, Japanese people are taught to value collective effort towards one cause. This is great for raising awareness, as even small actions can have a big effect and eventually lead to a movement.

One project which exemplifies this is PIRIKA, a smartphone app that helps you keep a log of the litter that you pick up on the street. In real-time, it visualizes the total amount of trash being collected by do-gooders around the world.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR DESIGN

This design brief asks: how can we make products and materials that are kept in use or regenerate natural systems? Take Tokyo’’s needs into account by considering the following opportunities.

- Take inspiration from existing products and practices. Furoshiki, the traditional wrapping cloth that is used to wrap clothing, goods, and gifts is a widely used, multi-purpose item. How can we design products that are similarly multi-functional, reusable and aesthetically pleasing?

- Japan has a strong tradition of creative design. How can we make products that are more modular and that can be repaired?

- In Japan, there are traditional crafts which are functional, beautiful, and which are made out of local, natural resources. Each item is made by artisans’ hands with sophisticated skills. How can we rethink traditional crafts and develop them to create additional value?

get inspired

ZIPLOC UMBRELLA SERVICE

The Ziploc Umbrella is not only an umbrella that is made from recycled ziploc bags, it is an umbrella sharing service as well. Asahi kasei, Nature Innovation Group, BEAMS and Terracycle joined forces for this collaborative project to produce a sustainable umbrella product and service. Users can pick-up the Ziploc Umbrella at one of the stands, use it when its pouring and return the umbrella when it stopped raining.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR DESIGN

This design brief asks: How can we use waste as a resource or dispose of goods more responsibly? Take Tokyo’s needs into account by considering the following opportunities.

- In Tokyo, you can argue that single-use products flow a little too quickly and efficiently to waste facilities. How can we create opportunities for items to be redirected and used as a valuable resource before they are considered waste?

- In Tokyo, we have food banks, but it is not well recognized or used. How can we better utilize this resource in order to reduce food loss?

- Japan was once a resourceful society, with an active recycling ecosystem. Today, there are only a few second-hand markets inTokyo for materials like apparel, automobiles, and electronics. How can we activate second-hand markets for more kinds of products and materials, like plastic and building materials?

GET INSPIRED

CREATING NEW AND SUSTAINABLE MARKETS

The ReBuilding Center in Nagona collects, sorts and organizes wood, furniture and tools from home demolition projects. By “rescuing” items that have lost their place in the world, they not only reduce the cost of transporting the waste, but also reduce their environmental impact. Customers can buy old wood that can be used to build or remodel homes, as well as products such as upcycled furniture. Meanwhile, the space brings together like-minded people and promotes a sense of community.

REFERENCES AND FURTHER RESEARCH

To learn more, here are the main sources used for creating this briefing:

-

History and Cultural Context

-

Everyday Things in Premodern Japan (English)

-

Waste; Consuming Postwar Japan (English)

-

Consuming Life in Post-Bubble Japan (English)

-

-

Data on Current Waste Problem

-

Government Policies on Sustainability (Climate Change and Waste Problem)

Tokyo selection committee

Akiyo Takada started Three Cs Co., Ltd. In 2007, she worked in the marketing & communication field for 40 years. Akiyo has been organizing various design/MARCOM projects, together with Ambassadors of Design, Japan (Tokyo-based NPO) and her company, to globalize Japan’s creative industries. She is also involved in various design competitions/promotions in Japan and overseas.

Amy Loo is a consultant at PwC Advisory with experience in corporate sustainability; past projects include supporting firms incorporate SDGs and ESG-related goals to their business plans and engaging broader stakeholders. She studied social and political aspects of urban planning and design as an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley. She is also the principal researcher involved in creating the Tokyo brief.

Hidenori Kondo is a Creative Producer and the Director of KYODO HOUSE, a house for community symbiosis. Since 2020, he has been involved in cross-disciplinary research and social implementation of creativity in an effort to achieve sustainable society at University of Creativity, a research institute for creativity. He has co-edited and co-authored several books, including Innovation Design and Urban Permaculture Guide, and has been a member of the Good Design Award selection committee from 2019.

Masaru Ito is the founder of SHIBAURA HOUSE in Tokyo. While running an advertising company that has been in business for 70 years, he opened the office to the public. It has a face of a community space for the neighborhood as well as a hub for cultural exchange, collaborating with various creative organizations overseas. Masaru enjoys building networks with exciting people.

Richard Van der Laken is a creative director based in Amsterdam. He met Pepijn Zurburg while studying at the Utrecht School of Art and Sandburg institute, and together they formed De Designpolitie – a renowned visual design agency, graphic design collective Gorilla, and What Design Can Do. Since forming, they’ve worked with many partners from Rabobank to Artis Zoo, won numerous awards, and feature in the permanent collection of galleries such as the Design Museum London and MoMa New York. At WDCD, they’ve created multiple design challenges, publications, and events hosted across Amsterdam, Brazil and Mexico. Richard is serving the Tokyo selection committee to represent What Design Can Do.

Ryoko Baba is an art program facilitator and Owner of ACU (Arts and Crafts Ukiha), a hub for multidisciplinary creative collaborations and networks.

After specializing in English translation and city promotion for 15 years in Fukuoka City, she moved to a pastoral area Ukiha in 2014. Ryoko has been organizing international art/cultural exchange programs with the help of Dutch Embassy since 2016. Ryoko has been creating opportunities for exchanges between international artists and the rural Japanese community. Ryoko has a BA in International Relations (Diplomacy).

Sander Wassink‘s non-functional creations can be viewed as paradigms that raise questions about the essence of appearances, functionality, transience and beauty, in a world overloaded with products and design. Sander studies production methods, distribution channels and sales strategies and the potential of alternative systems. His work is held in various museum collections, among them the Princessehof Ceramics Museum and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

Theo Peters is a graduate of Rikkyo University and entered the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1992. He was stationed in Jakarta, Tokyo, Brussels before being appointed as ambassador to the Netherlands in Senegal.

In August 2019 he returned to Japan as minister plenipotentiary of the embassy. He also heads the Public Diplomacy, Political and Cultural Affairs and is in charge of the implementation of the International Cultural Policy of the Dutch government in Japan.

Yoshiharu Tsukamoto graduated from the Department of Architecture of the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1987. He was a guest student of L’ecole d’architecture, Paris, Bellville from 1987 to 1988, and completed course work without a degree from the Post-Graduate School of Tokyo Institute of Technology. He founded Atelier Bow-Wow with Momoyo Kaijima in 1992 and has been active in a variety of fields, including architecture, public space, furniture design, field survey, education, art exhibition, curation, and writing. He is a proponent of behaviorology, an ecological turn in architectural design, which seeks to bring architecture back to people and communities from the side of industry.

SVP Tokyo is a network of more than 100 of engaged philanthropists (Partners) that aims to accelerate social entrepreneurship in Japan. Founded in 2003, SVP Tokyo joined SVP International officially in 2006 as its first Asian affiliate. Not only giving away our financial resources, we do contribute our professional know-how of each partner for up to 2 years to social entrepreneurs who tackle all kinds of social challenges.